For medical students of the future, one day there could be a new science on their Step 1 exams.

Traditionally, students are schooled in two core science areas—basic science and clinical science. But the work of the AMA's Accelerating Change in Medical Education initiative has helped push to the surface the need for a third: health care delivery science.

Defining the third core science

There have been rumblings of the need for such education for years, educators at the AMA's recent consortium meeting at Oregon Health and Science University said.

For this area of study, which often includes “systems-based practice,” quality improvement and practice-based learning, students must demonstrate awareness of the “larger context and systems of health care and the ability to call on system resources to provide care that is of optimal value,” according to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

But what does that mean?

“New skills are required for the changing health care marketplace, from interprofessional teams to payment reform to health IT,” said Jeffrey Borkan, MD, chair of family medicine at the Warren Alpert Medical School at Brown University. “Now, there's greater recognition that there is a gap, and we must equip students.”

This new third science ideally would include curricula on health care policy and economics, clinical informatics and health IT, population and public health, socioecological determinants of health, value-based care, and health system improvement. It also would incorporate teachings in leadership, teamwork, critical thinking and professionalism.

Med students looking for additional education

The need for such education isn't only recognized by academic physicians.

“While health care delivery science is resonating with the educators in this room, it's also resonating with the students as a perceived need,” said Grayson Armstong, a fourth-year medical student at Brown and chair of the AMA Medical Student Section.

Armstrong said in an informal poll of a panel of medical students, most indicated the interest in—and need for—curricula on economics, policy and health systems.

“If we're going to be agents of change, you have to have an understanding not only of the basic laws and rules of how health care works but the external forces that shape it,” said Nate Friedman, a second-year medical student at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine. “What we get [in school now] tends to be a little drier, or a little bit more down in the weeds. We know labs are expensive—but why are they expensive? How did we get there?”

Schools adopting the new science

Mayo Medical School is moving forward with such curricula in its Science of Health Care Delivery program, which covers specific content with a combination of face-to-face education and online modules. The school is developing tools to document student achievement in these new topic areas, including surveys, quality improvement reviews, patient safety knowledge assessments and checklists.

Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine launched its new systems navigation curriculum last year with its first-year students. The first part of the two-pronged curriculum will incorporate systems-based practice topics over a 17-month period.

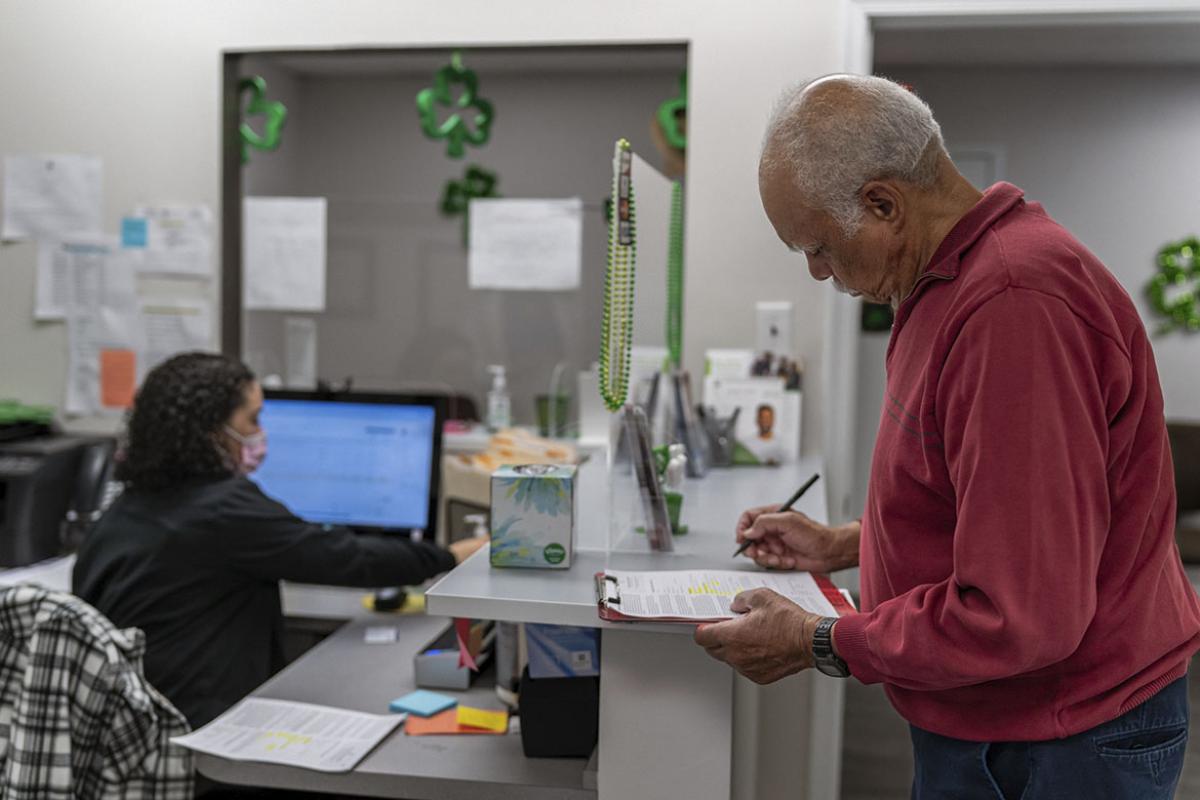

The second part will make the students “patient navigators,” linking them with local clinics to give the students experience in actually dealing with systems-based practice. As navigators, students will help patients handle insurance, find community resources and coordinate complex care issues.

The consortium's goal is to have curricula, competencies and assessments in the new third science mapped out so other medical schools can begin incorporating these principles into their programs. The group is using existing research and conducting its own research to push the idea of health care delivery science to the forefront.

The physician of the future really needs to be a person who understands what the issues are for a patient, their family, and their community, and brings the best resources to bear on problem solving,” said Susan Skochelak, MD, group vice president for medical education at the AMA. “They have to manage information. They have to provide leadership. They have to provide coaching, and they really have to focus on health for the patient, the family, and their community.”