Lora Wilkerson does not have to look far to see the potential effect of the Senate’s ongoing efforts to overhaul the nation’s health system. The Charleston, West Virginia, woman needs only peer into the bright eyes of her 3-year-old granddaughter, Ellie.

The girl was diagnosed at 18 months old with rhabdomyosarcoma, a rare cancer that mostly affects children. Wilkerson said Ellie is still alive because of the Medicaid coverage and patient protections available under the current health care law, provisions that the latest version of the Senate’s Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017 (BCRA) would overturn.

“Ellie would have died,” Wilkerson said at a press event held Thursday in Charleston. “Ellie survives, but continues to have nerve damage in her hands and feet.” The girl receives physical, occupational and speech therapy on a weekly basis.

Little Ellie is just one of more than 180,000 West Virginians now covered by Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Their coverage is threatened by the BCRA provision that would phase out the enhanced rate at which the federal government funds Medicaid expansion between 2021 and 2023. Expanded Medicaid makes coverage available to people who earn too much to qualify for the traditional Medicaid program but earn less than 138 percent of the federal poverty line (that is $28,180 for a family of three in West Virginia).

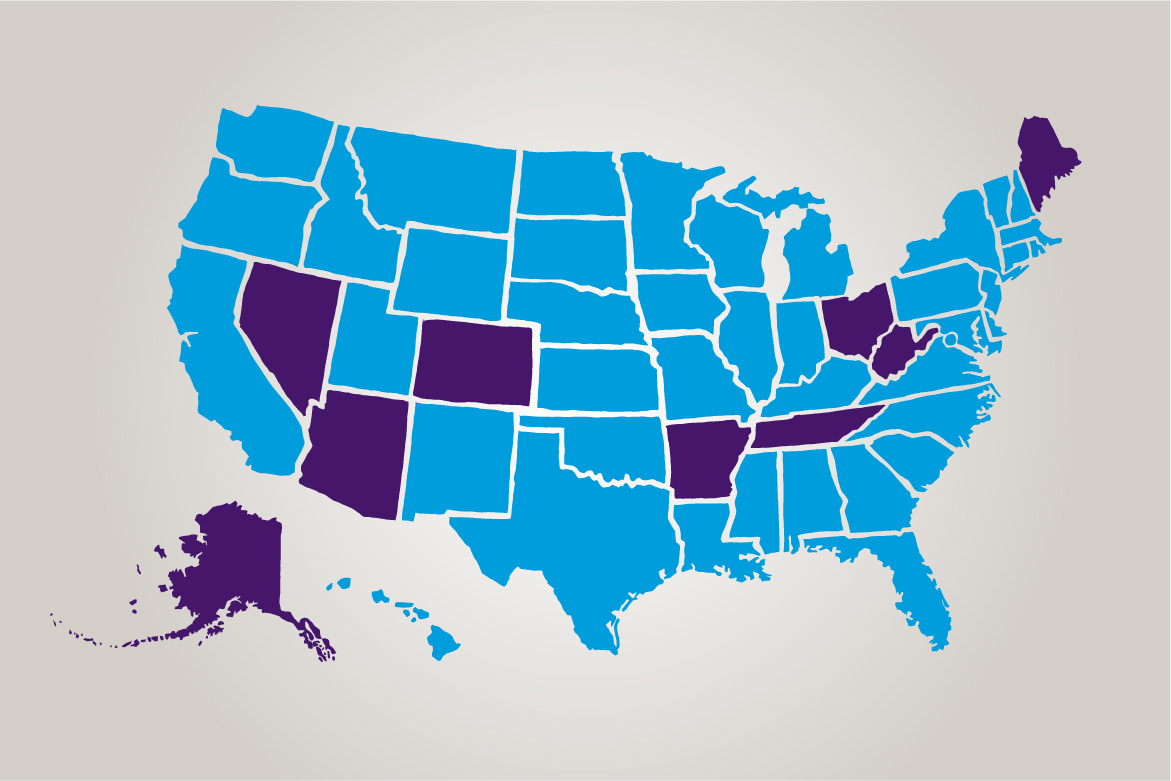

Nationwide, more than 14 million Americans have Medicaid coverage in 32 states that have opted for the program expansion that is endangered by the BCRA, which the AMA opposes. And in six other key states whose senators could decide the fate of this legislation, more than 2 million people have expanded Medicaid coverage that could disappear:

- Ohio: 682,900

- Colorado: 425,500

- Arizona: 418,400

- Arkansas: 303,900

- Nevada: 203,900

- Alaska: 14,400

There is another way that Ellie’s access to essential care could be hindered by the BCRA. If her parents’ income grew to the point where they were no longer eligible for Medicaid, they might seek insurance in the individual marketplace. In that event, Ellie would be penalized for her pre-existing condition—rhabdomyosarcoma—or her parents would face higher premiums and out-of-pocket costs due to lower subsidies and benefit standards.

In nine health care battleground states—the seven above plus Maine and Tennessee—more than 11.2 million people are estimated to have pre-existing conditions that would have been the basis for a medical underwriting denial of coverage prior to the ACA. In West Virginia, nearly 40 percent of residents fall into this unfortunate category. In Tennessee and Arkansas, one in three patients do. In Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, Ohio and Maine, more than 20 percent of patients have pre-existing conditions.

How a safety net could become a sieve

Perhaps the biggest impact of the BCRA would come about because of proposed changes to the traditional Medicaid program enacted in 1965. The proposed legislation would cap federal funding based on the number of patients enrolled in a state’s Medicaid program, starting in 2020. Payment increases would grow at the rate of medical inflation until 2025, when they would grow at the lower, non-medical inflation rate.

Such an approach would hamper access to care for the country’s most vulnerable patients—the poor, children, patients with disabilities and seniors who rely on the program to help pay for nursing-home or long-term care. As the Academy of Actuaries recently noted, this dramatic reshaping of the program could have dire effects.

Health care costs, these experts noted, are driven not just by factors such as the number of patients enrolled “but also by utilization increases, new treatments (e.g., costly biological drugs recently made available) and unexpected events such as natural disaster or pandemics.”

The caps would lead states to make “efforts to close budget gaps including eligibility and benefit changes may reduce Medicaid spending, but they will not reduce total spending.” Rather, the Academy wrote in a June 30 letter to Senate leaders, “the cost of care will be transferred to providers, insurers, employers and to the individuals who seek needed care.”

The BCRA’s arbitrary Medicaid funding formula would make it difficult for states to address public health epidemics or pay for breakthrough treatments that save or dramatically improve the quality of the lives of the country’s most vulnerable patients.

In the nine battleground states below, more than 10 million patients are covered by the traditional Medicaid program—a vital safety-net program that could become transformed into a sieve:

- Ohio: 3 million

- Arizona: 1.9 million

- Tennessee: 1.7 million

- Colorado: 1.3 million

- Arkansas: 767,000

- Nevada: 592,400

- West Virginia: 510,200

- Maine: 272,100

- Alaska: 137,800

In many of these states, Medicaid covers a large share of the children who live in small towns and rural areas, according to a recent report from the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families. In some of these states, majorities of such children rely on Medicaid to access the care they need to grow into healthy adults. In Arkansas, six in 10 children in small towns or rural areas are covered by Medicaid. In Arizona, the program covers 54 percent of these children. In West Virginia, the figure is 51 percent.

It figures, then, that recent polling found that support for cutting Medicaid is abysmal in seven of these states, ranging from 9 percent in Tennessee to 17 percent in Alaska. In West Virginia, the vast majority of those polled say they or someone they know is covered by Medicaid.

For Katie Coombs of Reno, Nevada, the staggering proportions of these kind of data underlie a deeper truth that elected officials should recognize. Coombs lives with supraventricular tachycardia and carries a defibrillator to get her heart back into rhythm as needed. She worries about how her pre-existing condition would be treated in a post-ACA world.

“I have a son who’s turning 2 today, and I need to be here for him for a long time,” Coombs told the Reno Gazette-Journal. “They need to understand the impact of the decisions they’re making. This isn’t just about winning or losing or repealing a law because you didn’t like the previous administration. This is about real people who have real concerns and have real health problems. And there are millions of us.”

Make your voice heard

Physicians and patients who want to engage in the advocacy campaign to preserve access to affordable and meaningful health insurance coverage are encouraged to visit the AMA's campaign website, at Patientsbeforepolitics.org. The site explores the AMA's health reform objectives in depth and provides resource documents, patient profiles and grassroots action links to facilitate communications with their Senators.

Read more about the AMA's comprehensive vision for health-system reform, refined over more than two decades by the AMA House of Delegates, which is composed of representatives of more than 190 state and national specialty medical associations. Or explore the AMA Wire® special series, “Envisioning Health Reform.”

- Key aspects of GOP health plans unpopular with battleground voters

- New effort puts reform’s focus on patient impact

- Federal funding for Medicaid program should not be capped: AMA

- Physicians get inside view of health reform debate at crossroads